Hi! How’s everyone doing? I’ve had a week that has seemed to last a month, although I did get a handle on things by Friday afternoon; but it did put me a bit behind on my blog cultivation.

Well, one does what one must. I like to engage in activities such as eating food, living inside in a building, and using electrical appliances and household fixtures, so I have to prioritize things. I am currently working on preparing a Trip Report post on my recent visit to Panglao Island in the Philippines – these posts have always been among the most popular on my older blogs – but in the meantime, I thought I’d share a slice of my professional life.

The following are a column I wrote on January 27 in criticism of a press release (which was uncritically copy-pasted as a news story by several media outlets) by one of the excessive number of “civil society” groups in the Philippines, the Institute for Climate and Sustainable Cities (ICSC). The folks at ICSC got big mad about that and prepared a Letter to Editor in response to it, which was published by The Manila Times on January 30. I welcome any response to anything I write, whether it comes to me individually or in the form of a public reaction, but of course I may respond to that as well, at my discretion, which I did in this case.

This is how public discourse is done, and while the specific topic may not mean much to my non-Filipino audience, I would like to think it is a good example of how people with disparate views on an issue can and should engage with one another.

***

The Reliability Double Standard (January 27, 2026)

Ben Kritz

Rough Trade

TODAY’S topic was sent to me over the weekend in the form of a very well-written commentary from a source in the local generation sector. It is important to keep in mind when reading this that this particular corporation has, along with substantial conventional generation capacity, extensive renewable energy assets, primarily grid-scale solar but in other forms as well, is aggressively expanding its RE portfolio, and generally adheres to the perspective that RE is the inevitable future of power supply. This, in fact, is a perspective shared across the entire Philippine generation sector, which is something self-appointed clean energy activists would realize if they engaged in rational dialogue, instead of behaving like attention-seeking clowns by casting energy development as class warfare.

Most of what follows is as I received it, with some of my own observations added. I believe it is an important point of view, and one that should be taken seriously by policymakers, would-be developers, regulators, and those who style themselves as watchdogs of the public good.

***

THE Institute for Climate and Sustainable Cities (ICSC) has found its latest villain. In a press release that was eagerly lapped up by the media last week, the climate group urged the Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC) to impose stiffer penalties on power plants that exceed their allowable outage limits. Their target, as always, is the country’s fleet of baseload coal and thermal plants, which they argue are prone to “unplanned outages” that threaten the grid.

On the surface, this sounds like a win for the consumer. Who wouldn’t want to punish a company for failing to keep the lights on? But scratch that surface, and you find a gaping logical hole that exposes the hypocrisy at the heart of our energy transition debate.

The ICSC and their allies are demanding strict punishment for the “unreliability” of thermal plants, while simultaneously advocating for a massive shift toward solar and wind—technologies that are, by definition, unreliable 50 to 80 percent of the time.

This raises a question that regulators seem terrified to ask: If we are going to fine a coal plant for breaking down, why are we giving a free pass to a solar plant for clouding over?

An outage is an outage

To the average Filipino household sitting in the dark, an electron is an electron. It does not matter if the blackout is caused by a boiler tube leak in a coal plant or a sudden drop in wind speed in the Visayas. The result—no power—is identical.

Yet, under the current narrative being pushed by environmental NGOs, these two failures are treated as moral opposites.

When a baseload plant trips, it is framed as a corporate failure, a sign of “aging infrastructure,” and a valid reason for massive financial penalties. But when a solar farm’s output collapses because of a rainstorm, or when wind turbines stop spinning during the summer doldrums, it is excused as “inherent variability.”

Why is “variability” treated as a valid excuse for non-delivery? If you order a package online and it doesn’t arrive, you don’t care if the delivery truck broke down (mechanical failure) or if the driver refused to drive in the rain (weather variability). You just know you didn’t get what you paid for.

Sweetheart deal

The ICSC’s call for penalties ignores the fact that renewable energy developers currently enjoy a regulatory “sweetheart deal.”

Baseload plants are contracted to provide 24/7 power. They are held to a standard of near-perfection. If they fall short of that promise, the ICSC wants them bled dry by fines. Meanwhile, variable RE sources like solar and wind are permitted to sign contracts that effectively say, “We will give you power when nature allows it. If we don’t, good luck.” This creates a perverse incentive structure. We are punishing the “workhorses” of the grid for stumbling while incentivizing the “show ponies” that only perform when conditions are perfect.

RE for the sake of RE

The policy implications of the ICSC’s proposal are deeply troubling. By demanding the economic crippling of thermal plants while coddling renewables, this proposal pushes for Renewable Energy for the sheer sake of RE—prioritizing ideological targets over the physical integrity of the total power system.

When regulators force intermittent energy onto the grid without mandating the necessary storage infrastructure, they erode overall grid stability. You cannot build a reliable, modern economy on the back of power generation that disappears at 6:00 PM. Pushing baseload plants into financial distress through heavy-handed penalties, before a viable 24/7 alternative exists, does not make the grid greener—it just makes it more fragile.

Realigning policy

It is time for the ERC and the Department of Energy to stop picking favorites. Policy and market signals should incentivize true reliability, a fair and transparent playing field, and affordability that delivers tangible benefits to the Filipino consumer.

Consumers do not pay their electricity bills for the vague promise of “salvation from extreme weather” or climate absolution; they pay for the lights to turn on when they flip the switch.

If the ICSC and the renewable sector are serious about market discipline, here is a modest proposal: Electron Neutrality.

The rule should be simple: If you sell power to the grid, you are responsible for delivering it. If a thermal plant trips, they pay. If a solar plant cannot deliver because of rain, they should pay. If renewable developers claim they can’t control the weather, the answer is technology, not exemptions. Battery storage exists. If they want to be treated as serious infrastructure players, they should be required to install energy storage to smooth out their own variance.

Until then, demanding stricter penalties for the backbone of our power supply while coddling the most intermittent sources isn’t “climate justice”—it is a regulatory shake-down.

***

The DOE has been flirting with the idea of making battery storage a required part of any new solar development, but has yet to implement that, for the simple reason that it is a turn-off to developers. Solar farms are comparatively cheap (although that may be changing soon); energy storage systems are not. Until that requirement is made, we have to question whether RE development policy really has a sustainable, reliable, and future-ready energy infrastructure as its end goal, or if it is indeed simply “RE for the sake of RE.”

***

28 January 2026

LETTER TO THE EDITOR

Renewable energy for the sake of energy security (January 30, 2026)

Dear Editor,

This is in response to the column titled “The Reliability Double Standard” written by Mr. Ben Kritz, published on January 27, 2026. While Mr. Kritz raises legitimate concerns about energy security, the piece conflates reliability with baseload capacity and misrepresents how the Philippine power system actually operates. More importantly, it overlooks the structural causes of today’s reliability challenges—baseload overcapacity, inflexible contracts, and poor risk allocation—while unfairly placing blame on renewable energy.

- For decades, Philippine power planning assumed electricity demand to be largely constant, justifying heavy investment in baseload generation. In reality, electricity demand varies significantly by hour and season, peaking between 9:00 AM and 9:00 PM. Analysis of the 2024 Luzon load profile shows off-peak demand, which is the basis of baseload capacity requirements, ranges from 6,000 to 9,000 megawatts (MW) while dependable baseload capacity exceeds 12,300 MW. This dependable baseload capacity is nearly equal to the system’s peak demand of about 13,700 MW, representing baseload overcapacity. This forces coal plants to ramp up and down daily, operating outside their optimal design parameters, which can result in accelerated wear and tear, degraded performance, and increased forced outages, even exceeding the ERC allowable outage limit.

- Coal and other thermal plants face additional pressures from global fuel price volatility and geopolitical risks. Yet inflexible Power Supply Agreements (PSAs) often guarantee payments regardless of actual delivery, while penalties for non-performance remain weak. This shifts both price and operational risk from generators to consumers.The Calaca coal power plants illustrate this problem. Despite Unit 2 being offline for nearly ten months each in both 2021 and 2022, company disclosures still showed profitability. This points to a deeper flaw in contract design: PSAs that reward capacity ownership rather than dependable performance. Such arrangements weaken accountability and undermine incentives for reliability.

- A pro-consumer regulatory regime is paramount to bring about meaningful change in the energy sector. Automatic fuel pass-through for coal should be removed as it allows cost spikes to be passed directly to consumers, weakens incentives for efficiency, and discourages prudent fuel risk management. PSAs must also be transparent, enabling the public to see the true cost of power and ensuring that payments reflect performance rather than guaranteed returns.

System reliability does not depend on any individual generator operating continuously for 24 hours. Instead, it depends on the grid’s ability, as a whole, to meet demand at all times despite these sources of variability. Thus, reliability today will not be achieved by adding more inflexible capacity, but by building a system that can respond to variable demand patterns through a balanced mix of baseload, intermediate, and peaking resources. This is obviously not the case in the Philippines, where baseload overcapacity leads to unplanned shutdowns and eventual grid alerts, which then result in higher electricity bills and the risk of power supply interruptions despite paying for “reliable” capacity.

Solar and wind plants are paid only for the electricity they actually generate during expected periods. Their variability is predictable, priced, and planned into system operations. This is fundamentally different from unplanned outages of large thermal plants, which remove capacity unexpectedly and destabilize the grid.

Critics frequently argue that renewable energy is unreliable because it is intermittent, and that coal plants are therefore indispensable for grid stability. This argument confuses variability with

unpredictability. Renewable output varies, but it does so in patterns that are forecastable,

scheduled, and explicitly accounted for in dispatch and contracts. Coal plant failures, by contrast, are unplanned, abrupt, and remove large blocks of capacity without warning—precisely the events that trigger grid alerts. A system built around resources whose behavior is known and planned is inherently more reliable than one that is dependent on large, inflexible units that fail unexpectedly.

Energy security ultimately depends on getting the energy mix right. For an archipelago like the Philippines, reliability comes from flexibility and diversity. Indigenous renewable resources— solar, wind, hydro, geothermal, and biomass—combined with energy storage, demand-side management, and a modernized grid, provide the ability to meet peak demand and improve system resilience. Renewable energy is not a liability—it is a predictable, strategically essential, and resilient component of the Philippine power system.

***

Does the ‘S’ in ICSC stand for “strawman?” (February 8, 2026)

Ben Kritz

Rough Trade

THE Institute for Climate and Sustainable Cities (ICSC) reacted with some pique to my column of January 27 (“The reliability double standard”) by filing a Letter to the Editor, which was published here in The Manila Times on January 30. I have said before that I appreciate considered responses – whether I agree with them or not – to any arguments I make in print, and I thank ICSC for taking the time to share their rebuttal. I regret not being able to address a few days earlier than now, but there have been intervening events.

That said, ICSC’s follow-up was a bit of a strawman argument, characterizing my piece as arguing in favor of maintaining coal-fired baseload capacity “while unfairly placing blame on renewable energy” for energy reliability challenges. The statement also makes a grossly erroneous argument in downplaying concerns about the variability of renewable energy, and while it calls out an admittedly consumer-unfriendly rate manipulation in the handling of fuel costs in conventional thermal plants, conveniently ignores the equally manipulative factors that burden consumers with the same sort of extra costs in RE plants.

First of all, just to clarify once again as I did when I originally published, the commentary that I shared in my January 27 column did not originate in my own appallingly brilliant mind, but was shared with me by a major generation company, one which has both extensive thermal and RE assets, and is pursuing an aggressive development program for the latter. In fact, provided those developments proceed more-or-less as planned, which they are so far, this company’s own energy mix will beat the national policy goal of having 35 percent RE by 2030 and 50 percent by 2040 by several years. This is obviously not a source that is in any way unenthusiastic about RE, and as I pointed out in my original column, it is quite representative of the Philippine generation sector as a whole in that respect.

This is another strawman argument of ICSC and other groups of that ilk, that the existing generation sector is resistant to RE development in favor of conventional baseload generation. It is simply not true.

ICSC’s letter also makes the assertion that, “For decades, Philippine power planning assumed electricity demand to be largely constant, justifying heavy investment in baseload generation.” This has led, ICSC argues, to excessive baseload capacity; about 12,300 megawatts (MW) versus the 6,000 to 9,000 MW it should be according to average off-peak demand. That is actually a fair point; overcapacity can be a handicap.

However, ICSC’s assertion implies that Philippine power planning is still being done according to conditions that were applicable “decades” ago. That is certainly not true at all; the DOE’s Green Energy Auction Program (GEAP) is a glowing rebuttal of that argument, as is the extensive RE generation development planning of major generation firms outside of the GEAP. RE as a significant primary source of generation capacity was not possible decades ago, and has only become so financially and technically in perhaps the last 10 years, and perhaps even less than that here in the Philippines. A half-century-old electricity infrastructure cannot be remade overnight; as I have said over and over again, because green energy advocates and consumer watchdogs evidently do not understand the meaning of the word, “transition” means a process of change over some period of time.

ICSC also makes a call, not for the first time, that automatic pass-through costs for coal should be disallowed, and the regulatory regime adjusted to remove this disincentive for efficiency and fuel cost risk management. I absolutely agree with that. However, as my original column stressed, all generation sources should be held to the same standards. In this case, the standard is, “not supported by regulatory perks that cushion prices against generators’ possible mistakes in management.” Take away fuel pass-through costs, certainly. But using the same reasoning, that means that subsidies to RE generators in the form of the feed-in tariff allowance (FIT-All) and the new Green Energy Auction Allowance (GEA-All) that all of us now pay beginning with January’s electric bill, should also be eliminated.

That above point about the pass-through costs, though it is valid, is where ICSC’s rebuttal started to really tick me off. Only coal is mentioned, which again makes the unfair and frankly rather offensive implication that the original commentary was pro-coal. There is more coal power in the Philippines than anything else, that is true, but coal is not the only fuel that is affected by cost volatility; natural gas, diesel, and bunker oil prices are generally more erratic than coal, and no less burdensome.

The most egregious and dishonest assertion in the ICSC response, however, was this absolute howler: “Renewable output varies, but it does so in patterns that are forecastable, scheduled, and explicitly accounted for in dispatch and contracts.” When multiple RE generation operators say that it is absolutely none of those things, one should take their word for it; after all, it is in their best interests to maintain as much uptime as possible, as they only get paid for the electrons they produce.

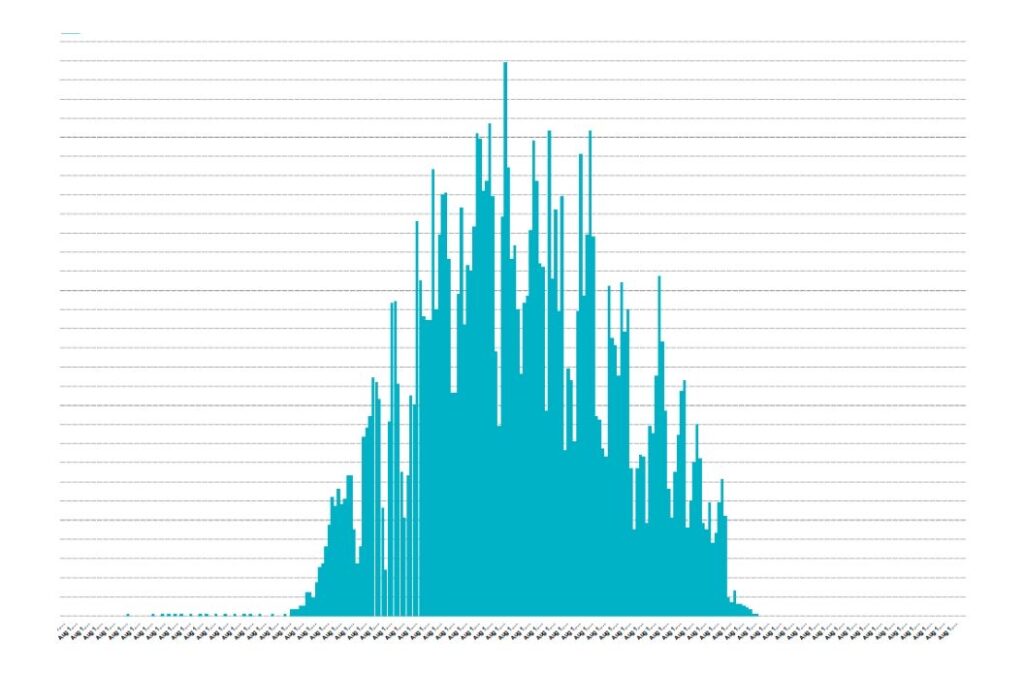

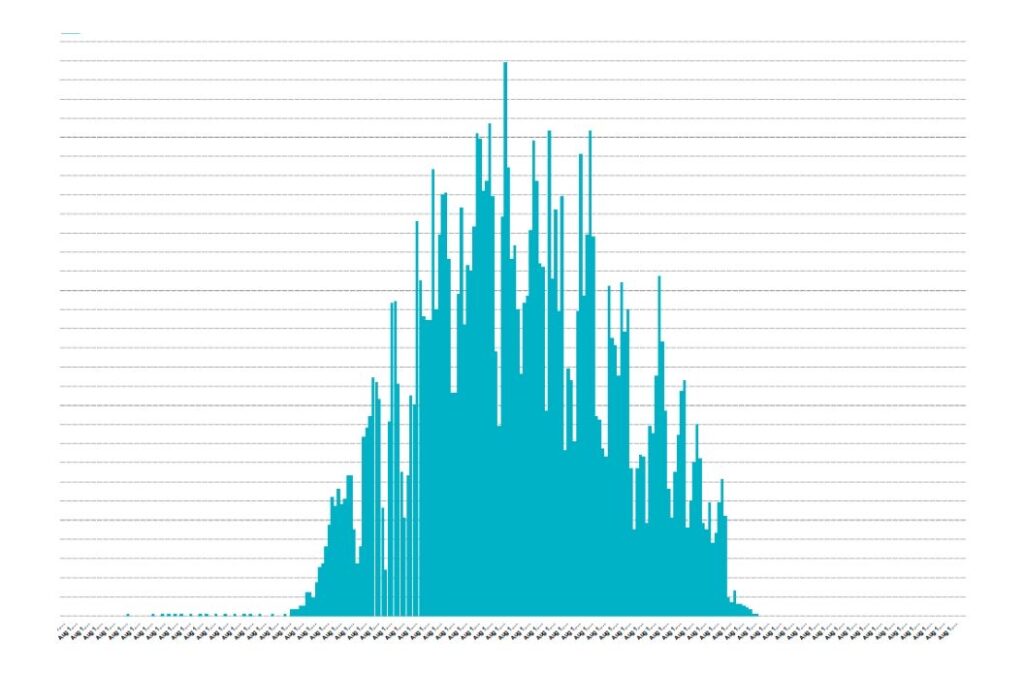

I’m going to issue a challenge to ICSC at this point. Below is a graphic, evidently supplied by Aboitiz Power from one of their own solar plants for inclusion in a recent article by PCIJ about offshore wind development, showing the generation output over a single day. Each bar represents a five-minute interval, corresponding to the dispatch intervals of the electricity spot market.

I would like to see ICSC’s researchers pick any existing utility-scale solar plant in the Philippines and produce month-ahead or even day-ahead forecasts that prove that the output is forecastable, and can be scheduled and explicitly accounted for in dispatch and contracts. Come up with a graph ahead of time that reasonably matches actual output next month or even tomorrow. I do not believe it can be done, and the people who actually run solar plants do not believe it, either. So here’s your chance to prove us wrong.